David Owen

July 4, 2016

Blacks in the Revolutionary War: Promises of freedom which fell short

Blacks were promised freedom from both the American and British sides. However, both sides fell short on the freedom issue after the War. The American side won the War but was out of resources. The British side lost the War but was rich in resources. Neither situation turned out to be very helpful to the Blacks in a comprehensive way. Having said that though, several thousand slaves won their freedom by serving on both sides of the War of Independence. As a result of the Revolution, a surprising number of slaves were freed (manumitted), while thousands of others freed themselves by running away in the turmoil of the War. In Georgia alone, 5000 slaves, a third of the colony’s prewar total, escaped. In South Carolina, a quarter of the slaves achieved freedom.

Widespread talk of liberty gave thousands of slaves high expectations, and many were ready to fight for a democratic revolution that might offer them freedom. In 1775 at least 10 to 15 black soldiers, including some slaves, fought against the British at the battles of Lexington and Bunker Hill. Two of these men, Salem Poor and Peter Salem, earned special distinction for their bravery. By 1776, however, it had become clear that the revolutionary rhetoric of the founding fathers did not include enslaved blacks. The Declaration of Independence promised liberty for all men but failed to put an end to slavery; and although they had proved themselves in battle, the Continental Congress adopted a policy of excluding black soldiers from the army.

In spite of these discouragements, many free and enslaved African Americans in New England were willing to take up arms against the British. As soon states found it increasingly difficult to fill their enlistment quotas, they began to turn to this untapped pool of manpower. Eventually every state above the Potomac River recruited slaves for military service, usually in exchange for their freedom. By the end of the war from 5,000 to 8,000 blacks had served the American cause in some capacity, either on the battlefield, behind the lines in noncombatant roles, or on the seas. By 1777 some states began enacting laws that encouraged white owners to give slaves for the army in return for their enlistment bounty, or allowing masters to use slaves as substitutes when they or their sons were drafted. In the south the idea of arming slaves for military service met with such opposition that only free blacks were normally allowed to enlist in the army.

Six years after the end of the American Revolution the heroism of black soldiers was not rewarded in the U.S. Constitution. The Declaration of Independence was signed July 4, 1776 and the U.S. Constitution was signed June 21, 1788. October 19, 1781 was the day the British surrendered in the American Revolution.

On the 200th anniversary of the U.S. Constitution, Thurgood Marshall, the first African American to sit on the Supreme Court, said that the Constitution was “defective from the start.”

Thurgood Marshall pointed out that the framers had left out a majority of Americans when they wrote the phrase, “We the People.” While some members of the Constitutional Convention voiced “eloquent objections” to slavery, Marshall said they “consented to a document which laid a foundation for the tragic events which were to follow.”

The word “slave” does not appear in the Constitution. The framers added protections TO SLAVERY, not AGAINST SLAVERY. The Constitution prohibited Congress from outlawing the Atlantic slave trade for twenty years. A fugitive slave clause required the return of runaway slaves to their owners. The Constitution gave the federal government the power to put down domestic rebellions, including slave insurrections.

It would not be until 1865 that amendments were started to be added to the Constitution which granted freedom for blacks. The 13th Amendment freed all enslaved people in the United States. The 14th amendment gave them full citizenship, and the 15th Amendment granted black men the right to vote.

The framers of the Constitution believed that concessions on slavery were the price for the support of southern delegates for a strong central government. They were convinced that if the Constitution restricted the slave trade, South Carolina and Georgia would refuse to join the Union. But by sidestepping the slavery issue, the framers left the seeds for future conflict. After the convention approved the great compromise, Madison wrote: “It seems now to be pretty well understood that the real difference of interests lies not between the large and small but between the northern and southern states. The institution of slavery and its consequences form the line of discrimination.”

Of the 55 Convention delegates, about 25 owned slaves. Many of the framers harbored moral qualms about slavery. Some, including Benjamin Franklin (a former slave owner) and Alexander Hamilton (who was born in a slave colony in the British West Indies) became members of antislavery societies.

source: http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/active_learning/explorations/revolution/revolution_slavery.cfm

related article and photos below: https://www.history.org/Foundation/journal/Autumn07/slaves.cfm

The First Rhode Island Regiment.

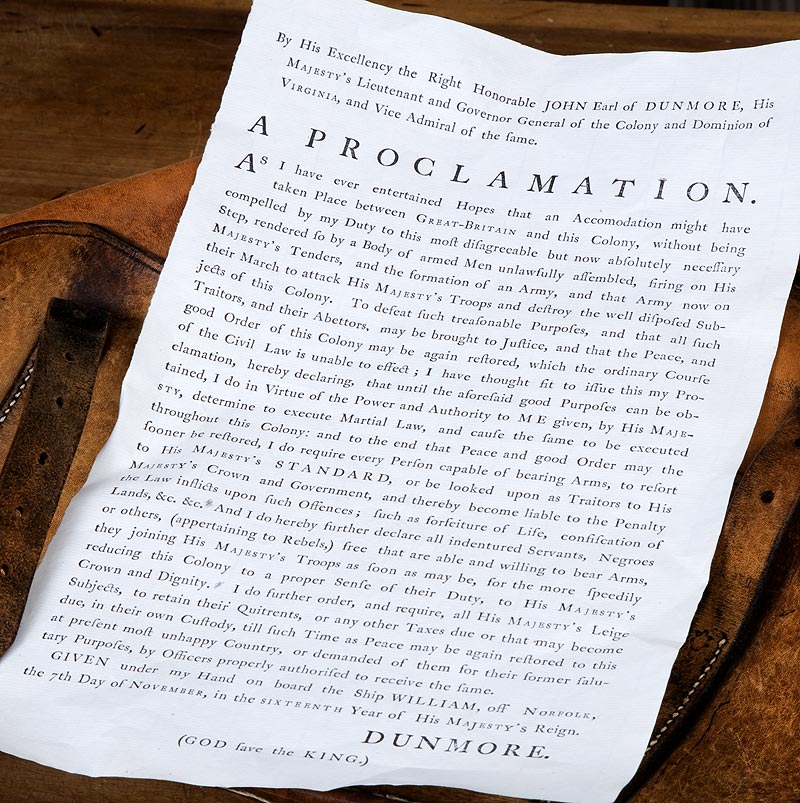

Governor Dunmore’s proclamation, reproduced above, offered liberty to male slaves of rebels if they fought their masters.

Governor Dunmore promised freedom for male slaves of rebels who joined British forces, but the offer secured lasting liberty for few. From left, Emily James, Hope Smith, Janine Harris, and Greg James debate the risks and promises of Dunmore’s proclamation.

Left to right, Jason Gordon, Richard Josey, with a copy of Dunmore’s proclamation, and Willie Wright approach a redcoat, here Stuart Pittman, to join the British forces and gain freedom. The prospect of enslaved blacks fighting slaveholders was meant to frighten colonists.

Video (Blacks in the Revolutionary War):