David Owen

September 29, 2016

Gabriel Prosser, born in 1776, was America’s Sparticus.

The Spartacus Slave Revolt was in 73 to 71 BC. Known more properly as the “Third Servile War,” this rebellion was led by Spartacus, a Thracian slave who fought as a gladiator. Spartacus led a revolt of gladiators against their Roman masters and gathered house and field slaves along the way in a massive uprising in which the Roman army experienced several losses. The Romans finally managed to put down the rebellion and executed as many as 6,000 of those captured by crucifixion. This rebellion is depicted in the 1960 movie Spartacus starring Kirk Douglas and in the television series Spartacus which was shown on the Starz cable premium channel from 2010 to 2013.

source: http://www.historyandheadlines.com/10-times-slaves-rose-masters/

It is fitting that Gabriel Prosser was born in 1776. Gabriel Prosser conspired to become a new Spartacus along with 1000 other slaves in Virginia in 1800. The rebellion was thwarted before it started but not the legend. The corollaries are numerous. Gabriel Prosser, a blacksmith skilled at making weapons. Gabriel Prosser, 6 feet, 2 or 3 inches tall and strong. Gabriel Prosser, literate and smart. Gabriel Prosser, free enough to socialize with all kinds of helpful people in the Richmond area and beyond. And Gabriel Prosser, unfortunately like Sparticus, executed for his deeds.

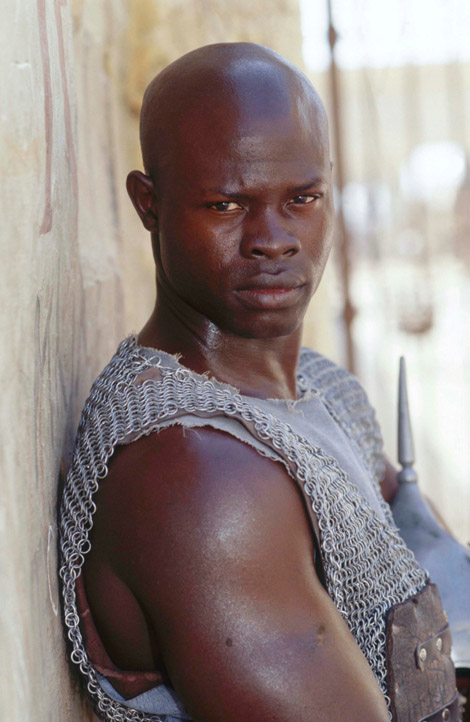

Djimon Hounsou in the movie, Gladiator

Gabriel’s Rebellion

Gabriel was born in 1776, on Thomas Prosser’s tobacco plantation in Henrico County, Virginia. When he was about ten, Gabriel and his brother Solomon began training as blacksmiths. Although almost nothing is known about Gabriel’s parents, it is likely that his father was a blacksmith, because skills were typically passed from generation to generation in Virginia slave families. As a child, Gabriel was also taught to read and write.

Gabriel was unusually intelligent, and unusually large; by the age of 20 he was six feet, two or three inches tall, and was enormously strong from his years of smithing. Even older slaves saw him as a leader.

Prosser died in 1798, and his son Thomas Henry Prosser, at the age of 22, became the new master of the Brookfield Plantation. Thomas Henry was a cruel and economically ambitious master, and it is likely that he pushed his slaves too hard. He also hired out some of his skilled slaves, including Gabriel and Solomon, a practice that was common in Virginia at the time — and one that allowed slaves more freedom than some Virginians were comfortable with. Although the state legislature made laws attempting to curtail hiring out, they were not enforced, largely because local merchants and artisans relied heavily on the cheap labor that they could get from hiring slaves, as opposed to white tradesmen.

Thomas Henry allowed Gabriel to hire himself out to masters in and around Richmond, giving him access to a certain amount of freedom, as well as money. Gabriel also met fellow hired slaves, free blacks, and white laborers, with whom he shared work and leisure time.

Many free blacks, though they faced overwhelming discrimination, managed to prosper as small business owners in the Richmond economy. Even more threatening to city authorities were the bonds that were formed among slaves, free blacks and working class whites, who worked and socialized together, especially in a city in which whites, and especially wealthy whites, were in the minority. Laws were passed curtailing socializing between slaves and free blacks, and interracial grog shops were raided.

Gabriel experienced several strong influences: the rhetoric of the American Revolution; the uprising in Saint Domingue, the radical words of white artisans who championed the working class; the success exhibited by free blacks; his own hatred of the merchants who routinely cheated the slaves they hired; his desire to be free and to prosper. He was moving toward a revolutionary stance that Solomon described in his court confession: “My brother Gabriel was the person who influenced me to join him and others in order that (as he said) we might conquer the white people and possess ourselves of their property.”

In September of 1799, Gabriel, Solomon, and a fellow slave named Jupiter stole a pig. When caught by white overseer Absalom Johnson, Gabriel wrestled him to the ground and bit off most of his ear. In court, he was found guilty of maiming a white man, a capital offense, but Gabriel escaped execution through a loophole called “benefit of clergy,” that allowed him to choose public branding over execution, if he could recite a verse from the Bible. Gabriel recited his verse, and then was branded in his left hand in open court. The branding, as well as the month he spent in jail, was the last in a long chain of offenses that pushed him toward open rebellion.

Inspired by Saint Domingue and spurred on by working-class talk of a truly egalitarian society, Gabriel decided it was time to act. He believed that if the slaves rose and fought for their rights, the poor white people would join them. His plan involved seizing Capitol Square in Richmond and taking Governor James Monroe as a hostage, in order to bargain with city authorities. According to later testimony, one of the conspirators also “was to go to the nation of Indians called Catawbas to persuade them to join the negroes to fight the white people.” It was also believed that a French “army was landed at South Key, which they hoped would assist them.” Their banner would bear the motto “death or Liberty,” the battle cry of Saint Domingue.

Gabriel conveyed his plan to Solomon and Ben, another of Prosser’s slaves, and the men began recruiting soldiers. They were later joined by other recruiters, most notably Jack Ditcher and Ben Woolfolk. The rebels did not include women in their army. While the majority of the men were slaves, the conspirators also drew free blacks and a few white workers to their cause, especially as they began recruiting in Richmond. Two Frenchmen and militant abolitionists, Charles Quersey and Alexander Beddenhurst, joined the ranks as leaders. A slave recruit named King, when told of the plot, said, “I was never so glad to hear anything in my life. I am ready to join them at any moment. I could slay the white people like sheep.”

The conspirators continued recruiting from Richmond and other Virginia towns, including Petersburg, Norfolk and Albemarle, and from the counties of Caroline and Louisa. After some difficulty, they were also successful in recruiting slaves from the Henrico County countryside. In this way they were preparing for the most far-reaching slave revolt ever planned in U.S. history. They also amassed weapons and began hammering swords out of scythes and molding bullets.

By August of 1800, Gabriel’s army was ready. Their plan, necessarily more elaborate now, included the taking of Norfolk and Petersburg by the men living there. Gabriel announced that they would move on the night of Saturday, August 30. As the lieutenants delivered news of the date to the outlying areas, a rumor of insurrection surfaced among Richmond whites, who reported it to Governor Monroe, who ignored it.

On August 30, a torrential rain began, described by James Callender, a person in jail for violating the sedition law, as “the most terrible thunder Storm… that I ever witnessed in this State.” A handful of men gathered at the appointed meeting spot, but it soon became clear that the quickly rising water would make key roads and bridges impassable.

The conspirators decided to postpone until Sunday evening, August 31. But before they had a chance to carry out their plan, slaves in two different locations cracked under the pressure and told their masters. Soon Governor Monroe was alerted, and white patrols, later joined by the state militia, began roaming the countryside searching for rebels. Gabriel and Jack Ditcher disappeared. Others eluded capture for several days, but by September 9, almost 30 slaves were in jail awaiting trial in the court of “Oyer and Terminer,” a special court in which slaves were tried without benefit of jury.

When the trials began on September 11, Gabriel and Ditcher were still at large, and white authorities had no idea of how extensive the insurrection had been. But white Virginians were terrified at the thought of how close the danger had come. One white fear, typical in times of black rebellion, was that black men were out to get white women.

One strategy that the white authorities used was to offer a full pardon to a handful of slaves who were willing to give testimony against the other conspirators. Gervas Storrs and Joseph Seldon, two of the court magistrates, found two key witnesses in this way: Ben, one of Prosser’s slaves, and Ben Woolfolk. Prosser’s Ben came forward first, and his testimony sent a number of slaves from his area to the gallows, including Gabriel’s brothers Solomon and Martin. But Prosser’s Ben did not have enough contact with slaves from the outlying areas, and so the court looked to Ben Woolfolk to give the damning evidence. Other slaves provided further testimony.

On September 14, Gabriel swam to a schooner called Mary on the James River. He asked to see the captain, a white man named Richardson Taylor. Two black men on board, Taylor’s former slave Isham and a slave named Billy, identified Gabriel as the leader of the plot. Though a former overseer, Taylor had apparently had a change of heart about slavery. He attempted to take Gabriel to freedom. However, when the ship docked in Norfolk, Billy alerted white authorities to Gabriel’s presence on board, no doubt thinking of the $300 reward being offered for Gabriel’s capture. Gabriel and Taylor were both arrested. Billy was rewarded, but not what he had expected. He received $50, far below what he needed to purchase his freedom.

On October 6, Gabriel was put on trial. Several witnesses came forward, but Gabriel himself refused to make a statement. He was sentenced to be executed the next day, but asked that his sentence not be carried out until October 10, so that he could be executed along with six other slaves who were to hang on that day. The court agreed, but on October 10 they hanged the slaves in three different locations; Gabriel was hanged alone on the town gallows.

In all, the trials lasted almost two months, and 26 slaves were executed by hanging; one more died by hanging while in custody. At least 65 slaves were tried; of those not hanged, some were transported to other states, some were found not guilty, and a few were pardoned. By law, slaveholders had to be reimbursed by the state for lost property, so in cases where slaves were executed or transported, their masters were reimbursed for their total worth declared by the court. Virginia paid over $8900 to slaveholders for the executed slaves.

Although most of the suspects were tried in Richmond, blacks captured in other counties were tried in those locations. Many of them shared the same fates as the Richmond slaves. However, in Hanover County, two slaves escaped with the help of blacks outside the prison and were never recovered. In Norfolk County, the magistrates questioned slaves and working-class whites alike, trying to find witnesses. But no one, including the accused slaves, would come forward with evidence, and the slaves were released. In Petersburg, four free blacks were arrested, but they too were released after the frustrated authorities could find no viable witnesses. There were slaves willing to give condemning evidence, but the testimony of slaves against free people was inadmissible in Virginia courts.

source: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part3/3p1576.html

The backlash was severe …

Gabriel’s slave conspiracy ended in severe repression. While no whites were killed in the revolt that never really got started, the state of Virginia executed 27 blacks, including Gabriel, by public hanging. Whites responded to the planned revolt, and another one linked to it in 1802, by tightening legal restrictions on slaves. For a brief period in the late 18th century white Virginians had modified certain elements of slavery.

Now many whites began to think that making the system slightly more humane had encouraged black resistance. As a result some of the advantages that slaves like Gabriel possessed were made illegal. For instance, literacy and allowing slaves to “hire out” for work in varied settings became illegal. Similarly, the Virginia legislature attempted to prevent enslaved people from piloting boats, a position from which they could travel too freely and learn about changes in the outside world that threatened white masters.

This newly repressive slave system was a tragic outcome for African-American collective action that had intended to liberate slaves. The reinvigorated slave societies of the south thrived in the 19th century and only ended with the massive violence of the Civil War. Nevertheless, the hypocrisy of slavery in a new nation dedicated to democracy was more obvious than ever before in American history. Though the brutal slave regime would continue to try and dehumanize the people it enslaved, it never fully succeeded.

As one member of Gabriel’s Rebellion explained during the trial that would ultimately sentence him to death, “I have nothing more to offer than what General Washington would have had to offer, had he been taken by the British and put to trial by them. I have adventured my life in endeavoring to obtain the liberty of my countrymen, and am a willing sacrifice in their cause.”

source: http://www.ushistory.org/us/20f.asp

… but the legend lives on.